Anti-Defection Law: Time for a Revamp

The Supreme Court recently criticized the Telangana Speaker for delaying decisions on MLA disqualification petitions. This has reignited the debate on the Anti-Defection Law (Tenth Schedule): the partisan role of the Speaker, loopholes created by the 'merger' provision, the impact on inner-party democracy, and proposals to shift adjudication power to an independent body like the Election Commission or a tribunal. This topic covers the evolution of the law, key Supreme Court judgments, committee recommendations and possible reform models.

Introduction

Context & Background

Key Points

- •Objectives of the Anti-Defection Law: The main aims were to (i) prevent political horse-trading and corruption, (ii) promote stability of elected governments, and (iii) protect party discipline so that policies placed before voters are not undermined after elections. It sought to make unethical individual defections politically and legally costly.

- •Grounds for Disqualification (Tenth Schedule): An MP/MLA can lose their seat if:

1. They voluntarily give up membership of their political party (this is interpreted broadly from conduct, not just formal resignation).

2. They vote or abstain from voting in the House contrary to the party’s whip, without prior permission and without later condonation by the party.

3. An Independent member (elected without party symbol) joins any political party after the election.

4. A Nominated member joins a political party after six months from the date on which they take their seat in the House. - •Scope of the Party Whip: In practice, parties issue whips for a very wide range of votes—not just for confidence/no-confidence motions or Budget, but also for ordinary legislation. This means legislators risk disqualification if they vote according to their conscience or their constituency’s interest against the party line, raising concerns about inner-party democracy and the role of individual MPs/MLAs.

- •The 'Merger' Exception – Key Loophole: A major escape route is the merger provision. If at least two-thirds (2/3) of a party’s legislators agree to merge with another party, they are deemed to have merged and are not disqualified. This has allowed mass defections to be engineered by persuading a sufficiently large group to cross over together. Legal experts argue that, logically, the merger should first occur between the original political parties outside the House, after which legislature parties may follow; but in practice, often only the legislature party 'merges', hollowing out the parent party within the House.

- •Role of the Speaker/Chairman: The Tenth Schedule vests the power to decide questions of disqualification on grounds of defection in the Speaker of the Legislative Assembly or the Chairman of the Council/House. In Kihoto Hollohan (1992), the Supreme Court upheld the validity of the law but held that the Speaker’s decision is subject to judicial review after it is made, since the Speaker acts as a Tribunal under the Tenth Schedule.

- •The Delay Problem: The Tenth Schedule does not prescribe any time limit for the Speaker to decide disqualification petitions. Speakers have often delayed decisions for months or years, particularly when defectors support the ruling party, thereby allowing them to continue as members and sometimes even ministers. In Keisham Meghachandra Singh v. Speaker, Manipur Legislative Assembly (2020), the Supreme Court observed that the Speaker should normally decide within three months, except in exceptional circumstances, but this guideline is not yet a binding statutory time limit.

- •91st Amendment Act, 2003 – Attempt to Tighten the Law:

1. Deleted the provision for 'split' (earlier 1/3rd of a party could break away without disqualification).

2. Introduced a cap on the size of the Council of Ministers at the Union and State levels to 15% of the strength of the Lower House (with a minimum of 12 ministers), to prevent indiscriminate creation of ministerial posts to reward defectors.

3. Provided that a legislator disqualified under the Tenth Schedule cannot be appointed as a minister until they are re-elected, thereby discouraging immediate political rewards for defection. - •Judicial Clarification on 'Voluntarily Giving Up Membership': In Ravi S. Naik (1994), the Supreme Court held that voluntary giving up membership is not limited to formally resigning from the party. It can be inferred from conduct such as openly criticising the party, attending rallies of a rival party, or accepting ministerial office with its support.

- •Recent Supreme Court Interventions: In several state-level crises (e.g., Uttarakhand, Arunachal Pradesh, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Telangana), the Court has had to step in to ensure floor tests, prevent abuse of the Governor’s office, and push Speakers to act on disqualification petitions. The Court has hinted that indefinite inaction by the Speaker can itself be unconstitutional and may justify intervention.

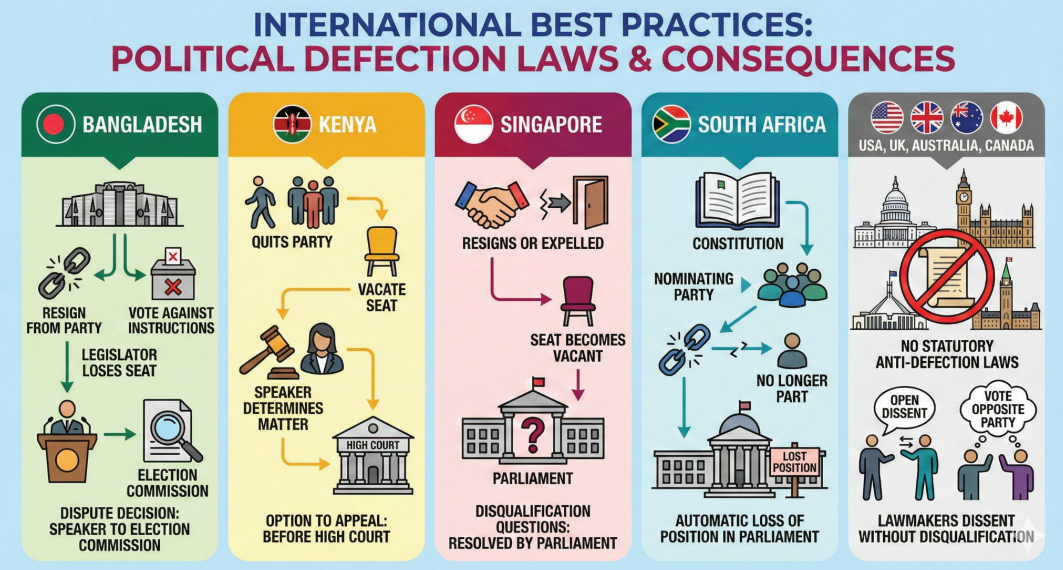

- •Comparative Perspective: Many parliamentary democracies (like the UK) do not have a strict anti-defection law. Legislators are generally free to vote against the party line, though they may face internal party discipline (loss of party position, denial of ticket) in the next election. India’s model is therefore more rigid and party-centric, designed to address the specific problem of frequent government instability in the 1960s–80s.

Supreme Court Judgments on Anti-Defection

| Case | Key Ruling | Bookmark |

|---|---|---|

| Kihoto Hollohan (1992) | Upheld the constitutionality of the Tenth Schedule but held that the Speaker’s disqualification order is subject to judicial review; Speaker acts as a Tribunal under the Schedule. | |

| Ravi S. Naik (1994) | Held that 'voluntarily giving up membership' can be inferred from a legislator’s conduct and is not confined to formal resignation from the party. | |

| Rajendra Singh Rana (2007) | Struck down the Uttar Pradesh Speaker’s inaction; held that failure to decide disqualification petitions in a reasonable time can amount to violation of constitutional duty. | |

| Keisham Meghachandra Singh (2020) | Observed that Speakers should decide disqualification petitions within a 'reasonable period', ideally within three months, to prevent misuse of the office. |

Reform Recommendations on Anti-Defection Law

| Committee/Body | Suggestion | Bookmark |

|---|---|---|

| Dinesh Goswami Committee on Electoral Reforms (1990) | Suggested that disqualification on grounds of defection should be decided by the President/Governor on the binding advice of the Election Commission, not by the Speaker. | |

| Law Commission – 170th Report (1999) | Recommended removing the 'merger' exception and restricting the operation of the law only to votes affecting the survival of the government (e.g., confidence/no-confidence motions). | |

| National Commission to Review the Working of the Constitution (NCRWC, 2002) | Suggested that defectors should be disqualified from holding any public office (including ministership) for the remainder of the term, to act as a strong deterrent. | |

| Various Constitutional Experts | Have argued for a non-partisan adjudicatory authority (independent tribunal or Election Commission) and for narrowing down the scope of the whip to only crucial votes. |

Key Concepts under the Anti-Defection Law

| Term | Meaning / Relevance | Bookmark |

|---|---|---|

| Whip | A written direction issued by a political party to its legislators to be present and vote in a specified manner; violation can lead to disqualification under the Tenth Schedule. | |

| Legislature Party | Group of elected members of a political party in the legislature; recognised for purposes of the Tenth Schedule when counting fractions like 2/3rd for merger. | |

| Split (Deleted by 91st Amendment) | Originally, if 1/3rd of members broke away, it was considered a legitimate split and members were not disqualified; this provision was misused and later removed. | |

| Merger | Current exception where if 2/3rd of the members of a legislature party agree to merge with another party, it is treated as a merger and members are exempt from disqualification. |

Related Entities

Impact & Significance

- •Political Stability vs. Representative Accountability: The law has undeniably reduced the frequency of individual defections and helped maintain stable governments. However, by binding legislators tightly to the party whip, it weakens their ability to independently represent their constituency’s interests or exercise ethical judgement, especially on ordinary policy matters.

- •Strengthening Party System, Weakening Inner Democracy: Anti-defection provisions have empowered party leaderships, making them central to legislative decision-making. Internal dissent is often suppressed, and legislators may become rubber stamps rather than deliberative representatives, impacting the quality of parliamentary debate.

- •Judiciary as a Check on Political Abuse: The Supreme Court’s repeated interventions signal that while the Court respects the Speaker’s office, it will not tolerate the use of procedural delays to subvert constitutional principles. This judicial oversight adds a layer of accountability but also reflects deeper design flaws in the law.

- •Electoral Integrity & Voter Trust: Defections can convert a minority mandate into a majority through backdoor methods. A robust and fair anti-defection framework is essential to ensure that the post-election composition of the House broadly reflects the mandate that voters gave.

- •Federal and State-Level Implications: State politics has seen frequent government changes through defections (Goa, Manipur, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, etc.). How the anti-defection law is reformed will significantly influence political stability and coalition dynamics at the state level.

Challenges & Criticism

- •Speaker’s Structural Bias: The Speaker is usually a member of the ruling party or coalition. While expected to act impartially, the institutional design makes complete neutrality difficult. When disqualification affects the survival of the government, the incentive to delay or selectively act is strong.

- •Merger Clause Confusion and Misuse: The continuing presence of the merger exception allows large-scale engineered defections to be legally shielded. There is ambiguity about whether the merger must first take place between original parties in the political arena or whether a mere legislative merger is enough.

- •Suppressing Legitimate Dissent: Because the whip can be issued for a wide range of votes, MLAs/MPs fear disqualification even for voting according to conscience. This undermines the concept of deliberative democracy and the principle that legislators are trustees for their constituents, not just agents of party high commands.

- •Legal Uncertainty and Delays: In the absence of a clear constitutional time frame, petitions linger, and litigation drags on. Interim arrangements (like allowing defectors to vote in trust votes) can alter political outcomes irreversibly, even if they are later disqualified.

- •Frequent Political Engineering: Despite the law, political parties have become more sophisticated in engineering defections through resignations, pre-planned 'mergers', and inducements for mass crossovers, indicating that the law’s deterrent value is limited in its current form.

Future Outlook

- •Independent Adjudicatory Mechanism: A widely supported reform is to transfer the power of deciding defection cases from the Speaker to an independent authority—for example, the Election Commission of India or a constitutionally created tribunal. This would reduce partisan bias and align adjudication with principles of natural justice.

- •Narrowing the Scope of Whip: Many experts recommend that the anti-defection law should apply only to votes that directly affect the stability of the government—such as confidence motions, no-confidence motions, and money bills—while allowing free voting on ordinary legislation and policy issues.

- •Clear Statutory Timelines: There is strong demand to incorporate a specific time limit (e.g., 30 or 60 days) in the Constitution or in the Rules for deciding defection petitions, with consequences if the deadline is deliberately violated.

- •Revisiting the Merger Clause: Options include (i) completely removing the merger exception, or (ii) tightly defining it so that it only applies when there is an actual party-level merger outside the House first, followed by legislature party alignment, thereby preventing merely numerical floor crossing.

- •Strengthening Internal Party Democracy: Long-term reform might involve incentivising political parties themselves to practise more internal democracy—transparent candidate selection, intra-party elections, and respect for internal dissent—so that defection pressures reduce.

- •Comprehensive Political Reform: Anti-defection reform must be seen alongside related reforms (party funding transparency, strong anti-corruption measures, independent appointments to constitutional offices) to reduce the incentives for unethical defections in the first place.

UPSC Relevance

- • GS-2 (Polity & Governance): Parliament and State Legislatures, role of the Speaker, Constitutional Amendments, functioning of the Tenth Schedule, relationship between legislature and judiciary.

- • GS-2 (Comparative Politics): Comparative understanding of party discipline and anti-defection norms in other parliamentary democracies.

- • Essay: Topics like 'Ethics in Politics', 'Crisis of Political Morality', 'Role of Institutions in Maintaining Democratic Stability', and 'Party System vs Inner Party Democracy'.

- • Prelims: Tenth Schedule basics, 52nd & 91st Amendments, key Supreme Court judgments, meaning of 'merger', 'split', 'whip', and the role of the Speaker under the Tenth Schedule.

Sample Questions

Prelims

Which one of the following Schedules of the Constitution of India contains provisions regarding anti-defection?

1. Second Schedule

2. Fifth Schedule

3. Eighth Schedule

4. Tenth Schedule

Answer: Option 4

Explanation: The Tenth Schedule, inserted by the 52nd Constitutional Amendment Act, 1985, lays down the grounds and procedure for disqualification of legislators on the ground of defection.

Mains

“The role of the Speaker in deciding disqualification petitions under the Tenth Schedule has come under serious scrutiny.” Discuss the major issues with the present anti-defection framework and suggest reforms in the light of judicial pronouncements and committee recommendations.

Introduction: Briefly introduce the Anti-Defection Law (Tenth Schedule, 1985) and the Speaker’s position as the adjudicating authority, highlighting recent controversies and Supreme Court remarks.

Body:

• Issues: Partisan role and structural bias of the Speaker; absence of statutory timelines leading to deliberate delays; misuse of 'merger' provision; stifling of legitimate dissent due to broad use of whips; frequent political engineering despite the law.

• Judicial Perspective: Kihoto Hollohan (upholding the law but allowing judicial review); Ravi S. Naik (broad view of voluntary giving up membership); Rajendra Singh Rana and Keisham Meghachandra (Speaker’s constitutional duty and need for time-bound decisions).

• Reform Proposals: Dinesh Goswami Committee and others advocating transfer of adjudicatory power to President/Governor acting on Election Commission’s advice or to an independent tribunal; narrowing the law’s operation to only confidence/no-confidence and money bills; revisiting or deleting the merger clause; codifying strict timelines and consequences for non-compliance.

• Balancing Stability and Democracy: Need to design a framework that prevents opportunistic defections while protecting inner-party democracy, freedom of expression of legislators and genuine representation of constituency interests.

Conclusion: Conclude that a carefully redesigned anti-defection regime, coupled with broader political and ethical reforms, is essential to restore public trust, strengthen democratic institutions and uphold the sanctity of the voter’s mandate.