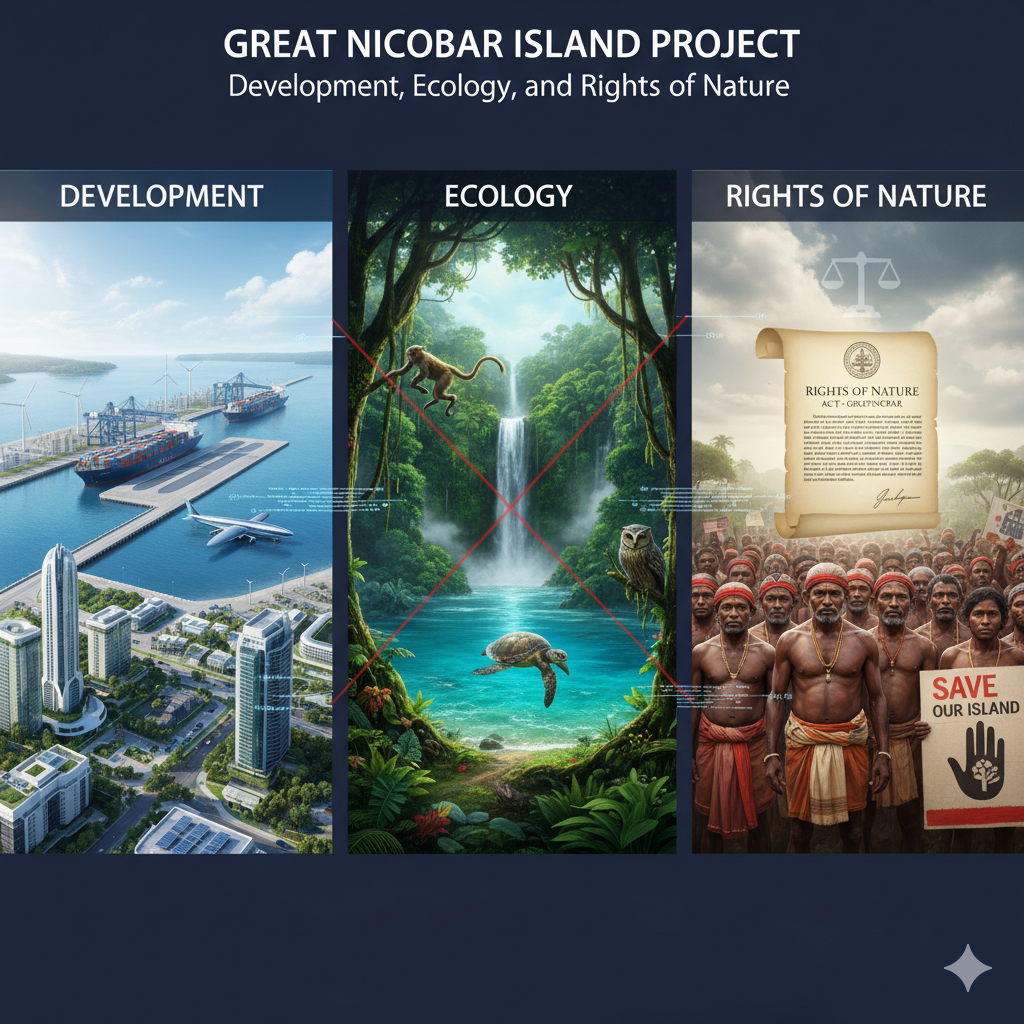

Great Nicobar Island Project: Development, Ecology and Rights of Nature

The Great Nicobar Island (GNI) Project — involving a massive transshipment port, power plant, township, and airport — has sparked a major debate about whether India’s development priorities are undermining fragile ecosystems, indigenous communities, and the emerging idea of granting legal rights to nature.

Introduction

Context & Background

Key Points

- •Biodiversity Hotspot: Great Nicobar hosts over 2,200 plant species, 270 bird species, and many endemic species found nowhere else. The Nicobar Megapode, leatherback turtles, saltwater crocodiles, and rare orchids flourish here. For beginners: a ‘biodiversity hotspot’ means a region with very high species diversity but under severe threat from human activities.

- •Marine & Coastal Ecology: The island is surrounded by coral reefs, mangroves, and seagrass meadows. These ecosystems act as natural shields against cyclones and tsunamis, reduce coastal erosion, and are breeding grounds for fish. Coral reefs around Havelock Island and Nicobar are among India’s richest, but highly sensitive to dredging, pollution, and climate change.

- •Strategic & Economic Rationale: The proposed deep-water port will lie close to the world’s busiest shipping route — the East-West maritime corridor, used for trade between Europe and East Asia. India argues that this will help bypass Singapore, create a global transshipment hub, and strengthen the presence of the Indian Navy in the Indo-Pacific. Additionally, the new airport and township are meant to boost tourism and create local jobs.

- •Scale of Ecological Impact: The project involves clearing about 130 sq km of pristine rainforest — almost the size of Chandigarh — with an estimated 10 million trees to be cut. Tropical rainforests develop over thousands of years, and once destroyed, they cannot be restored easily.

- •Threat to Endangered Species: Galathea Bay is one of the last remaining large nesting beaches of the Leatherback Sea Turtle, the world’s largest turtle. Construction in this area could disrupt future nesting, violating India’s Marine Turtle Action Plan (2021).

- •Disaster Risk: Great Nicobar sits in Seismic Zone V, the highest risk category in India. Heavy infrastructure such as a port, township, and airport in a tsunami-prone zone increases the risk to human life and reduces the island's natural resilience.

- •Indigenous Communities: The Shompens and Nicobarese have unique lifestyles based on forest produce, horticulture, and coastal resources. Their cultural identity is closely tied to the island’s ecology. Large-scale land diversion threatens their livelihoods, health, and cultural knowledge.

- •Compensatory Afforestation: The proposal to compensate for this deforestation by planting trees in Haryana or Madhya Pradesh is scientifically flawed. Plantation trees cannot replace the ecological richness of tropical rainforests, which host thousands of species and act as massive carbon sinks.

- •Niyamgiri Precedent (2013): The Supreme Court ruled that Gram Sabhas (village assemblies) have the final say in forest diversion decisions where tribal religious and livelihood rights are affected. This is crucial because the GNI project also affects tribal rights protected under the Forest Rights Act, 2006.

- •Rights of Nature Concept: Around the world, countries like Ecuador and New Zealand have granted legal personhood to rivers and forests, allowing them to be represented in court. This shifts the legal perspective from humans owning nature to nature having its own rights.

- •Indian Experience: In 2017, the Uttarakhand High Court declared the Ganga and Yamuna rivers as living entities. Although the Supreme Court stayed this decision, it expanded India’s conversation on ecocentric environmentalism.

- •Guardianship Model: Under Rights of Nature, ecosystems have human representatives called guardians who speak on behalf of the river, forest, or landscape in legal and policy decisions — similar to how minors have legal guardians.

Ecological Sensitivity Overview of Great Nicobar Island

| Category | Key Features | Why It Matters | Bookmark |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biodiversity | Over 2,200 plant species, 270 bird species, endemic fauna like the Nicobar Megapode | High risk of permanent species extinction due to deforestation | |

| Marine Ecosystems | Coral reefs, mangroves, seagrass meadows around Campbell Bay & Galathea Bay | Protects coastlines, supports fisheries, acts as natural climate buffer | |

| Indigenous Communities | Shompens (PVTG) & Nicobarese dependent on forests and marine resources | Displacement threatens traditional knowledge & cultural survival | |

| Disaster Vulnerability | Located in Seismic Zone V; worst-hit during 2004 Tsunami | High exposure to earthquakes & tsunami hazards | |

| Protected Areas | Great Nicobar Biosphere Reserve & Campbell Bay National Park | Legally protected under Wildlife Protection Act & UNESCO MAB |

Environmental Cost of Major Components of the GNI Project

| Project Component | Purpose | Environmental Cost | Bookmark |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transshipment Port | Create an alternative to Singapore/Malacca route; strengthen Indo-Pacific trade presence | Large-scale dredging, coral reef destruction, turtle nesting disruption | |

| International Airport | Defense logistics + support for tourism and economic activity | Habitat loss, noise disturbance, large land diversion in forest zones | |

| Gas-based Power Plant | Provide 450 MVA power for township, port, and industrial activities | Thermal pollution, freshwater stress, increased CO₂ emissions | |

| New Township | Accommodate over 3 lakh residents including workers, officers, and defense personnel | Massive land-use change, water scarcity, waste disposal challenges |

Related Entities

Impact & Significance

- •Strategic & Economic Impact: The project could improve India’s maritime presence near the Strait of Malacca, one of the world’s most important shipping chokepoints. It may boost logistics, naval security, and regional development. However, benefits must be balanced against the irreversible ecological cost.

- •Ecological Impact: Large-scale deforestation will lead to habitat fragmentation, affecting species movement. Mangrove destruction weakens natural flood barriers. Coral reef loss will reduce fish populations and increase coastal vulnerability.

- •Social & Cultural Impact: Tribal communities risk losing not only land but also identity, traditional knowledge systems, and cultural heritage. Forced displacement or cultural assimilation violates constitutional protections for Scheduled Tribes.

- •Environmental Governance: This project tests India’s commitment to sustainable development, environmental democracy, and tribal rights under the Constitution, FRA 2006, and biodiversity laws.

- •Legal Innovation: Recognising Great Nicobar as a legal entity could help ensure stronger, long-term protection by allowing the ecosystem to defend itself in court against destructive actions.

- •Global Image: India’s actions on Great Nicobar will influence how the world views India’s claims of climate leadership and ecological responsibility under the Paris Agreement and biodiversity conventions.

Challenges & Criticism

- •Ecological Irreversibility: Once old-growth tropical forests are destroyed, their complex biodiversity and microclimates cannot be recreated. This could permanently alter the island’s ecology.

- •Violation of Conservation Commitments: The project threatens species protected under India’s Wildlife Protection Act and Marine Turtle Action Plan. It may also violate international obligations under the Convention on Biological Diversity.

- •Tribal Rights Concerns: The Forest Rights Act guarantees tribal control over traditional lands. Critics argue that Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) has not been meaningfully taken from the Shompen and Nicobarese communities.

- •Questionable Compensatory Afforestation: Planting trees in mainland states does not compensate for the loss of primary rainforest, which supports thousands of species and unique ecological processes.

- •Disaster-Prone Siting: The island’s high seismicity and tsunami risk make the construction of major infrastructure risky, exposing populations to natural disasters intensified by climate change.

- •Weak Monitoring & Transparency: Experts argue that Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) were rushed, with inadequate scientific data and limited public participation.

- •Rights of Nature vs. Growth Model: The development approach appears anthropocentric (human-centered), prioritising economic growth over ecological well-being. Rights of Nature proposes a shift to an eco-centric approach.

Future Outlook

- •Development should adopt a phased, low-impact model with strict EIAs for each stage and constant environmental monitoring.

- •Strategic infrastructure must avoid critical habitats and use green engineering such as elevated structures or low-impact coastal designs.

- •Indigenous communities such as the Shompens and Nicobarese should be recognised as co-custodians of forests and marine ecosystems, ensuring benefit-sharing and cultural preservation.

- •Tourism and shipping should follow Blue Economy principles — reef-safe tourism, strict CRZ norms, and sustainable fisheries.

- •Coastal structures must incorporate tsunami models, sea-level rise predictions, and mangrove buffers for resilience.

- •Monitoring must be conducted by independent scientists, tribal representatives, and civil society, ensuring transparency.

- •Compensatory afforestation should occur within the same ecological region to maintain biodiversity integrity.

- •India can follow the Colombia Atrato River bio-cultural rights model, granting Great Nicobar its own legal guardians to protect the ecosystem.

UPSC Relevance

- • GS-1: Biodiversity hotspots, tribes of India, island geography.

- • GS-2: Rights of indigenous peoples, environmental governance, judicial interventions.

- • GS-3: Conservation, EIA, disaster management, sustainable development, Blue Economy.

- • Essay: Climate justice, rights of nature, balancing economy and ecology.

Sample Questions

Prelims

With reference to the Great Nicobar Island and the Rights of Nature discourse, consider the following statements:

1. Great Nicobar Island is part of a biodiversity hotspot and falls in a high seismic zone.

2. The Great Nicobar Biosphere Reserve includes important nesting sites for the leatherback sea turtle.

3. Compensatory afforestation for the GNI Project is proposed entirely within the Nicobar Islands.

4. The idea of granting legal personhood to natural entities has been recognised in some foreign jurisdictions.

Answer: Option 1, Option 2, Option 4

Explanation: Compensatory afforestation is proposed in mainland states, not within Nicobar. Other statements are correct.

Mains

The Great Nicobar Island Project highlights the tension between strategic development and ecological justice. In this context, discuss how the emerging concept of ‘Rights of Nature’ and existing Indian legal precedents can reshape environmental governance for such projects.

Introduction: The Great Nicobar Island Project involves extensive infrastructure in a fragile ecosystem inhabited by indigenous tribes. It raises concerns about sustainability and the adequacy of existing legal frameworks.

Body:

• Ecological & Social Concerns: Massive deforestation, threat to leatherback turtles, seismic risk, and displacement of Shompen and Nicobarese communities.

• Indian Legal Frameworks: Forest Rights Act and Niyamgiri judgment emphasise tribal consent and cultural protection.

• Rights of Nature: Global trend treating ecosystems as legal persons; ensures independent ecological representation.

• Application to GNI: A guardianship model involving tribes, scientists, and government bodies can safeguard ecological interests.

• Way Forward: Phasing the project, transparent EIA, in-situ conservation, and integration of bio-cultural rights.

Conclusion: Embedding Rights of Nature principles within Indian environmental governance can help balance strategic needs with ecological justice.