Economics Playlist

18 chapters • 0 completed

Introduction to Economics

10 topics

National Income

17 topics

Inclusive growth

15 topics

Inflation

21 topics

Money

15 topics

Banking

38 topics

Monetary Policy

15 topics

Investment Models

9 topics

Food Processing Industries

9 topics

Taxation

28 topics

Budgeting and Fiscal Policy

24 topics

Financial Market

34 topics

External Sector

37 topics

Industries

21 topics

Land Reforms in India

16 topics

Poverty, Hunger and Inequality

24 topics

Planning in India

16 topics

Unemployment

17 topics

Chapter 15: Land Reforms in India

Chapter TestLand Reforms in India

Land reforms are steps taken by the government to make land ownership fairer and more equal. Earlier, in India, most land was owned by a few big landlords, while poor farmers had very little or no land. Land reforms tried to solve this problem by redistributing land, protecting tenants, consolidating fragmented land, and creating proper land records. The aim was to help poor farmers, reduce inequality, and improve agriculture.

Land reforms are steps taken by the government to make land ownership fairer and more equal. Earlier, in India, most land was owned by a few big landlords, while poor farmers had very little or no land. Land reforms tried to solve this problem by redistributing land, protecting tenants, consolidating fragmented land, and creating proper land records. The aim was to help poor farmers, reduce inequality, and improve agriculture.

Mains Key Points

Prelims Strategy Tips

Bhoodan Movement

The Bhoodan (land-gift) Movement was started in April 1951 by Acharya Vinoba Bhave in Pochampally village, Telangana. Its purpose was to reduce rural poverty by persuading wealthy landowners to voluntarily donate part of their land to poor and landless farmers.

The Bhoodan (land-gift) Movement was started in April 1951 by Acharya Vinoba Bhave in Pochampally village, Telangana. Its purpose was to reduce rural poverty by persuading wealthy landowners to voluntarily donate part of their land to poor and landless farmers.

Bhoodan vs Gramdan – A Comparison

| Aspect | Bhoodan | Gramdan |

|---|---|---|

| Meaning | Voluntary donation of land by landlords to poor farmers | Entire village land becomes collective property |

| Started | 1951, Pochampally (Telangana) | 1952, first village Magroth (U.P.) |

| Process | Landlords donate part of their land | 75% villagers with 51% land must agree in writing |

| Objective | Reduce landlessness | Egalitarian redistribution & joint cultivation |

| Impact | Raised awareness but limited redistribution | Very few villages implemented it successfully |

Mains Key Points

Prelims Strategy Tips

Phases of Land Reforms in India – First Phase (1949–72)

The first phase of land reforms in India (1949–72) focused on abolishing the exploitative Zamindari system, introducing land ceilings, and protecting tenancy rights. These reforms were influenced by the recommendations of the Kumarappa Committee (1949). The most important step was the Zamindari Abolition Act, 1950, which transferred ownership rights from landlords to tenants.

The first phase of land reforms in India (1949–72) focused on abolishing the exploitative Zamindari system, introducing land ceilings, and protecting tenancy rights. These reforms were influenced by the recommendations of the Kumarappa Committee (1949). The most important step was the Zamindari Abolition Act, 1950, which transferred ownership rights from landlords to tenants.

Key Features of First Phase of Land Reforms

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Committee | Kumarappa Committee (1949) – recommended zamindari abolition, land ceiling, tenancy reforms |

| Major Law | Zamindari Abolition Act, 1950 |

| Beneficiaries | Tenant farmers, occupancy tenants, small cultivators |

| Challenges | No compensation, rent disputes, weak implementation, concentration of land continued |

| Constitutional Support | 1st Amendment (1951), Article 31B, Ninth Schedule |

Mains Key Points

Prelims Strategy Tips

Tenancy Reforms in India

After the abolition of Zamindari, the next focus of land reforms was tenancy regulation. Before independence, tenants had to pay very high rents (35–75% of their produce). Tenancy reforms aimed to give tenants security, reduce rent, and in some cases, grant them ownership of the land they cultivated.

After the abolition of Zamindari, the next focus of land reforms was tenancy regulation. Before independence, tenants had to pay very high rents (35–75% of their produce). Tenancy reforms aimed to give tenants security, reduce rent, and in some cases, grant them ownership of the land they cultivated.

Tenancy Reforms – Key Aspects

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Main Aim | Protect tenants, regulate rent, give ownership |

| Fair Rent | Reduced to 1/4 – 1/6 of produce |

| Security of Tenure | Tenants cannot be evicted arbitrarily |

| Ownership Rights | Granted in Kerala, West Bengal, some other states |

| Challenges | Political resistance, oral tenancy, legal hurdles |

Mains Key Points

Prelims Strategy Tips

Ceiling Laws in India

Ceiling laws were land reform measures that fixed an upper limit on how much land a person or family could legally own. Any land above this ceiling was taken by the state and redistributed to the landless. The idea was to prevent concentration of land in the hands of a few and promote social justice.

Ceiling laws were land reform measures that fixed an upper limit on how much land a person or family could legally own. Any land above this ceiling was taken by the state and redistributed to the landless. The idea was to prevent concentration of land in the hands of a few and promote social justice.

Ceiling Laws – Key Features

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Main Objective | Prevent land concentration, redistribute surplus land |

| Ceiling Variation | 6 acres (Kerala, wet land) to 336 acres (Rajasthan, dry land) |

| Unit of Application | Family (Kerala, Rajasthan) vs Individual (Bihar, MP) |

| National Guidelines 1972 | 10–18 acres (best land), 18–27 (second class), 27–54 (others) |

| Challenges | Benami transfers, poor records, weak administration, high ceilings |

Mains Key Points

Prelims Strategy Tips

Second Phase of Land Reforms (1972–1985)

The second phase of land reforms in India focused on land distribution, land consolidation, and increasing productivity. This was also the time of the Green Revolution, when modern agricultural practices, HYV seeds, and irrigation expanded rapidly.

The second phase of land reforms in India focused on land distribution, land consolidation, and increasing productivity. This was also the time of the Green Revolution, when modern agricultural practices, HYV seeds, and irrigation expanded rapidly.

Second Phase of Land Reforms – Key Points

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Time Period | 1972–1985 |

| Focus | Land distribution and consolidation |

| Linked With | Green Revolution, HYV seeds, IADP |

| Methods of Consolidation | Voluntary (cooperatives), Compulsory (Punjab, Haryana) |

| Key Benefits | Higher productivity, irrigation, mechanisation, reduced disputes |

Mains Key Points

Prelims Strategy Tips

Challenges of Land Consolidation & Need for Re-Consolidation

Land consolidation faced many hurdles such as lack of political support, emotional resistance of farmers, and poor documentation. Progress was uneven across states. Today, with shrinking farm sizes (from 2.28 ha in 1970–71 to 1.08 ha in 2015–16), re-consolidation is necessary to enable investments, mechanisation, and rural development.

Land consolidation faced many hurdles such as lack of political support, emotional resistance of farmers, and poor documentation. Progress was uneven across states. Today, with shrinking farm sizes (from 2.28 ha in 1970–71 to 1.08 ha in 2015–16), re-consolidation is necessary to enable investments, mechanisation, and rural development.

Challenges vs Solutions in Land Consolidation

| Challenge | Explanation / Example |

|---|---|

| Uneven Progress | Punjab & Haryana successful, others like Rajasthan & Tamil Nadu lagged |

| Emotional Resistance | Farmers unwilling to give up even tiny plots |

| Fertile vs Infertile land | Exchanges unfair if quality reduced |

| Oral Tenancies | Lack of written records slowed process |

| Fragmentation Today | 2.5 ha split into 32 tiny plots in Bihar family |

Mains Key Points

Prelims Strategy Tips

Third Phase of Land Reforms (1985–1995)

This phase of land reforms shifted focus from land redistribution to conserving natural resources like soil and water. It introduced programmes such as the Desert Development Programme (DDP), Drought Prone Areas Programme (DPAP), and Integrated Wastelands Development Programme (IWDP) to fight drought, desertification, and wasteland degradation.

This phase of land reforms shifted focus from land redistribution to conserving natural resources like soil and water. It introduced programmes such as the Desert Development Programme (DDP), Drought Prone Areas Programme (DPAP), and Integrated Wastelands Development Programme (IWDP) to fight drought, desertification, and wasteland degradation.

Key Programmes of Third Phase (1985–95)

| Programme | Main Aim | Coverage | Funding |

|---|---|---|---|

| DDP (1977–78) | Stop desertification, improve desert economy | Sandy, non-sandy, cold deserts | 75:25 Centre:State, 100% Centre in UTs |

| DPAP | Mitigate drought, restore ecology, create jobs | 627 blocks, 96 districts in 13 states | 75:25 Centre:State, 100% Centre in UTs |

| IWDP (1989) | Rehabilitate wastelands, restore ecology, improve livelihoods | 167 districts, 18 states, 27.88 million ha | 75:25 Centre:State, 100% Centre in UTs |

Mains Key Points

Prelims Strategy Tips

Fourth Phase of Land Reforms (1995 onwards)

This phase shifted focus from land redistribution to modernizing land administration. Emphasis was on digitization of land records, improving land revenue administration, and ensuring clarity of ownership through programmes like Digital India Land Records Modernization Programme (DILRMP) and SVAMITVA Scheme.

This phase shifted focus from land redistribution to modernizing land administration. Emphasis was on digitization of land records, improving land revenue administration, and ensuring clarity of ownership through programmes like Digital India Land Records Modernization Programme (DILRMP) and SVAMITVA Scheme.

Fourth Phase of Land Reforms – Key Programmes

| Programme | Year | Main Aim | Key Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| DILRMP | 2008 | Digitization of land records, conclusive titling | Real-time, transparent ownership records |

| SVAMITVA | 2020 | Drone mapping, property validation in villages | Property cards, reduced disputes, monetisation |

Mains Key Points

Prelims Strategy Tips

SVAMITVA, Bhumi Samvaad, ULPIN and LARR Act 2013

From 1995 onwards, land reforms in India shifted towards better land governance, digitization of records, property validation, and fair land acquisition. Key initiatives include SVAMITVA (property cards in villages), Bhumi Samvaad (digital land records dialogue), ULPIN (Bhu-Aadhaar for land parcels), and LARR Act, 2013 for fair compensation and rehabilitation.

From 1995 onwards, land reforms in India shifted towards better land governance, digitization of records, property validation, and fair land acquisition. Key initiatives include SVAMITVA (property cards in villages), Bhumi Samvaad (digital land records dialogue), ULPIN (Bhu-Aadhaar for land parcels), and LARR Act, 2013 for fair compensation and rehabilitation.

Comparison: Land Acquisition Act 1894 vs LARR Act 2013

| Aspect | 1894 Act | LARR Act 2013 |

|---|---|---|

| Public Purpose | Vague, govt. discretion | Clearly defined purposes |

| Consent | No consent needed | 80% (private), 70% (PPP) |

| Compensation | Minimal, based on old circle rates | 4x rural, 2x urban market value |

| Dispute Settlement | No provision, courts clogged | State dispute settlement authorities |

| Return of Land | No return provisions | Unutilised land (5 years) must return |

| Rehabilitation | Only monetary compensation | Mandatory relief & rehab, esp. SC/ST |

| Agricultural Land | No restriction | Multi-crop fertile land protected |

Mains Key Points

Prelims Strategy Tips

Issues with LARR Act 2013 and the 2015 Amendment Bill

The LARR Act 2013 was seen as progressive for ensuring fair compensation, consent, and rehabilitation. However, its strict requirements caused delays, disputes, and policy paralysis. To address these, the government proposed the LARR Amendment Bill, 2015, but it faced political resistance.

The LARR Act 2013 was seen as progressive for ensuring fair compensation, consent, and rehabilitation. However, its strict requirements caused delays, disputes, and policy paralysis. To address these, the government proposed the LARR Amendment Bill, 2015, but it faced political resistance.

Comparison: LARR Act 2013 vs Amendment Bill 2015

| Aspect | LARR 2013 | LARR Amendment 2015 |

|---|---|---|

| Consent | 80% for private, 70% for PPP projects | Five project categories exempted from consent |

| Participation | SIA mandatory for all projects (except urgency cases) | Exemption for five project categories |

| Land Use | Multi-crop land only as last resort, state to set limits | Exempted for five categories |

| Compensation | 13 central Acts exempt for 1 year | Aligned 13 Acts with LARR provisions |

| Accountability | Dept. head deemed guilty if offence | Dept. head not automatically guilty, sanction required |

| Return of Land | 5 years fixed | Later of 5 years or project-specific period |

| Private Sector | Only 'private companies' | 'Private entity' includes trusts, partnerships, NGOs etc. |

| Rehabilitation | Job to one family member | Job clarified – includes farm labour family members |

Mains Key Points

Prelims Strategy Tips

Criticism of LARR Amendment Bill 2015 and Agricultural Land Leasing & Contract Farming Reforms

The 2015 Amendment to the Land Acquisition Act faced criticism because it reduced the strong protections that farmers had under the 2013 Act. At the same time, reforms like the Model Agricultural Land Leasing Act (2016) and Model Contract Farming Act (2018) were introduced to make farming more secure, reduce risks for farmers, and attract investments.

The 2015 Amendment to the Land Acquisition Act faced criticism because it reduced the strong protections that farmers had under the 2013 Act. At the same time, reforms like the Model Agricultural Land Leasing Act (2016) and Model Contract Farming Act (2018) were introduced to make farming more secure, reduce risks for farmers, and attract investments.

Reforms Overview (Simple Comparison)

| Reform | Easy Explanation |

|---|---|

| 2015 Bill Criticism | Reduced farmer safeguards, broad exemptions, misuse risk |

| Model Land Leasing Act 2016 | Legal renting of farmland, owner protected, tenant gets loans/insurance |

| Contract Farming | Farmer & buyer sign deal → fixed price & supply |

| Model Contract Farming Act 2018 | Protects farmer, excludes APMC fees, fast dispute resolution |

Mains Key Points

Prelims Strategy Tips

Forest Rights Act, 2006 (Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers Recognition of Forest Rights)

The Forest Rights Act (FRA) 2006 recognises the rights of forest-dwelling Scheduled Tribes (FDSTs) and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (OTFDs) over land and forest resources. It aims to correct historical injustices caused by colonial forest laws which denied communities their traditional rights. It empowers Gram Sabhas to decide claims and provides secure rights to individuals and communities.

The Forest Rights Act (FRA) 2006 recognises the rights of forest-dwelling Scheduled Tribes (FDSTs) and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (OTFDs) over land and forest resources. It aims to correct historical injustices caused by colonial forest laws which denied communities their traditional rights. It empowers Gram Sabhas to decide claims and provides secure rights to individuals and communities.

Forest Rights Act 2006 – Key Features

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Eligibility | STs and OTFDs living in forests for 75 years or 3 generations |

| Land Rights | Up to 2.5 hectares per family (recognition, not new allocation) |

| Community Rights | Minor forest produce, grazing, water bodies, traditional uses |

| Core Areas | Provisional rights for 5 years; permanent if relocation not done |

| Gram Sabha Role | Identifies claimants, verifies rights, recommends to authorities |

Mains Key Points

Prelims Strategy Tips

Evaluation of Land Reforms in India

Land reforms in India had mixed results – they ended zamindari and reduced inequalities, but failed to fully redistribute land due to loopholes, poor records, and political resistance. After 1991, new challenges arose like industrialisation, displacement, and shrinking farm sizes.

Land reforms in India had mixed results – they ended zamindari and reduced inequalities, but failed to fully redistribute land due to loopholes, poor records, and political resistance. After 1991, new challenges arose like industrialisation, displacement, and shrinking farm sizes.

Evaluation of Land Reforms – Key Points

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Agricultural Productivity | Redistribution, direct farming, consolidation boosted yields |

| Social Equity | Abolished intermediaries, reduced inequality, encouraged cooperation |

| Success Factors | Freedom struggle awareness, strong laws, farmer movements, judiciary support |

| Limitations | Political resistance, poor land records, loopholes, weak administration |

| Post-1991 Challenges | Industrialisation, displacement, shrinking farms, wastelands |

Mains Key Points

Prelims Strategy Tips

Swamitva Scheme and National Land Monetization Corporation (NLMC)

The Swamitva Scheme is a government initiative launched in 2020 to provide clear ownership records of residential land in rural India using modern technology like drones. It aims to reduce disputes, improve financial access, and strengthen local governance. Alongside, the National Land Monetization Corporation (NLMC) was established in 2022 to manage and monetise surplus land owned by the government and public sector companies.

The Swamitva Scheme is a government initiative launched in 2020 to provide clear ownership records of residential land in rural India using modern technology like drones. It aims to reduce disputes, improve financial access, and strengthen local governance. Alongside, the National Land Monetization Corporation (NLMC) was established in 2022 to manage and monetise surplus land owned by the government and public sector companies.

Swamitva Scheme and NLMC – Key Aspects

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Launch Date (Swamitva) | 24 April 2020 (Panchayati Raj Diwas) |

| Implementing Ministry | Ministry of Panchayati Raj |

| Technology Used | Drones, GIS mapping |

| Coverage (as of now) | 6 states |

| Launch Date (NLMC) | 3 June 2022 |

| Ownership (NLMC) | Fully Government of India-owned |

| Objective (NLMC) | Monetisation of surplus land and closure of loss-making CPSEs |

Mains Key Points

Prelims Strategy Tips

Modern Technologies in Land Survey and DILRMP

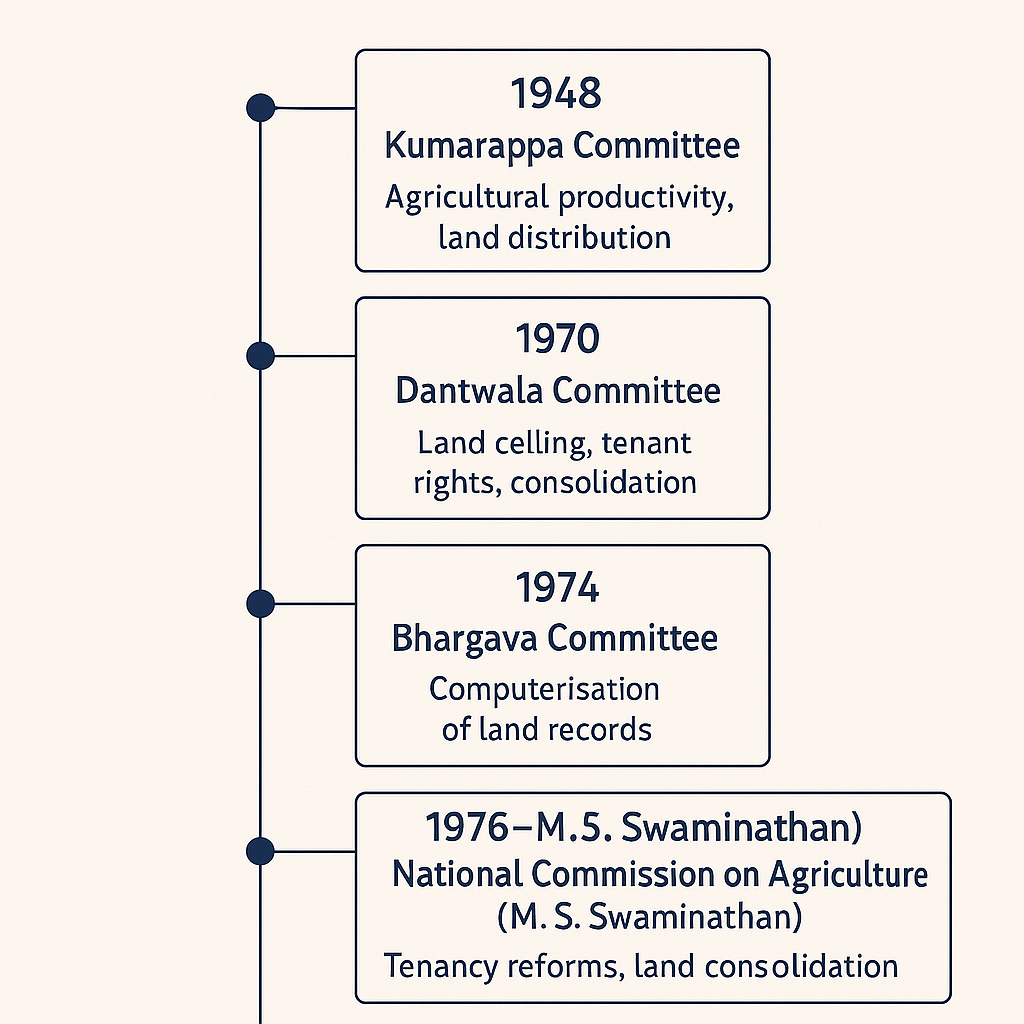

The Government of India is focusing on digitising land records to ensure transparency, reduce disputes, and make land management efficient. An international workshop highlighted the use of drones, aerial photography, and 3D imagery in urban land surveys. The Digital India Land Records Modernization Programme (DILRMP) and new initiatives like ULPIN and NGDRS are central to this mission. Several committees since independence have guided land reforms in India.

The Government of India is focusing on digitising land records to ensure transparency, reduce disputes, and make land management efficient. An international workshop highlighted the use of drones, aerial photography, and 3D imagery in urban land surveys. The Digital India Land Records Modernization Programme (DILRMP) and new initiatives like ULPIN and NGDRS are central to this mission. Several committees since independence have guided land reforms in India.

DILRMP and Land Reform Committees – Key Aspects

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Workshop Host | Ministry of Rural Development |

| Pilot Project | NAKSHA – Urban land survey in 100+ cities |

| DILRMP Launch | 1 April 2016 (Central Sector Scheme) |

| Key Innovations | ULPIN (Bhu-Aadhaar), NGDRS (E-registration) |

| Kumarappa Committee (1948) | Agricultural productivity, land distribution |

| Dantwala Committee (1970) | Land ceiling, tenant rights, consolidation |

| Bhargava Committee (1974) | Computerisation of land records |

| NCA – Swaminathan (1976) | Tenancy reforms, land consolidation |

| Hanumantha Rao (1979) | Surplus land distribution, farmer support |

| Abhijit Sen Committee (2008) | Land records, ceiling laws, tribal land issues |

Mains Key Points

Prelims Strategy Tips

Chapter Complete!

Ready to move to the next chapter?